Hieratic was a version of Egyptian hieroglyphics that developed in parallel with hieroglyphics.

While the question of “is it a writing system or isn’t it?” has come up several times already in these postings, hieratic is interesting because it brings up a slightly different question: “is it a distinct writing system or isn’t it?”

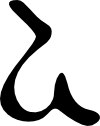

Hieroglyphics were used for relatively formal use, and frequently carved in stone. Hieratic script was written with a brush and ink on papyrus or cast-off pottery or limestone shards for less formal texts. There is almost a one-to-one correspondence between hieroglyphic glyphs and hieratic glyphs, but they don’t look very much alike. They look like different writing systems.

However, cursive and printed Latin script don’t look very similar, either:

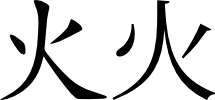

It turns out that there are a number of writing systems that have similar-but-not-quite-the-same characters. For example, the Chinese glyph for fire looks like a person with their arms up. The version of that glyph most commonly used in Japan is similar, but the angle of one of the “arms” is flipped for the version most commonly used in Japan:

Just as an English-reader would probably say that the cursive “r” and the printed “r” are the same character, Japanese and Chinese readers would probably agree that the “Chinese” and “Japanese” versions of “fire” are the same character.

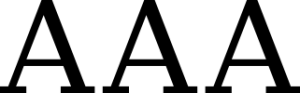

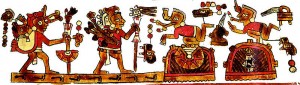

Now look at these. You might think they are from the same writing system:

In fact, they are not. The left one I got from Greek, the middle from Latin, and the rightmost from Cyrillic. You might say, “ah, but they are the same basic character because they represent the same basic sound, a vowel that is pronounced something like ‘ah’.”

That doesn’t work for this glyph:

This character is not a vowel pronounced something like “ah”, it is a syllable pronounced “go” from Cherokee. This is clearly from a different writing system than Latin (or Greek or Cyrillic).

Thus, design similarity does not determine if something is a distinct writing system or not. Hieratic looks very different from hieroglyphics, but I think it is nonetheless not a separate writing system. It’s more like a crazy-different font.

Links: Wikipedia, Ancient Scripts, Omniglot