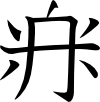

Pahlavi (Psalter) "s" and "h"

As a result of Alexander the Great tromping through Central Asia, Greek deposed Imperial Aramaic as the official language of the region. However, although Alexander might have been great, didn’t have much staying power: he died at age 32. His empire splintered messily after his death, and the majority of the empire dumped Greek after the dust settled.

In the area of modern Iran, Middle Persian filled the void left by Greek’s exit, although Aramaic was still very popular as a spoken lingua franca. To write Middle Persian, they used a script called Pahlavi, which was descended from Aramaic, but they kept using the Aramaic script in to write Middle Persian as well. Even when writing in the Pahlavi script, they used a lot of Aramaic words as logograms: they wrote the words in the Aramaic script in the middle of Pahlavi script, but pronounced them as Middle Persian words. (This is similar to how Sumerian written words were still used in Akkadian, Assyrian, and Hittite.) It would be as if when the collection of symbols “шляпа” showed up in the middle of English texts, they would be pronounced as “hat”.

Middle Persian is an Indo-European language, so vowels are much more important than in the Semitic Aramaic. Despite having what were, in my opinion, many obviously better options that must have been well known (different glyphs for vowels like Greek or decorations for vowels like in Brahmi), the Middle Persians instead elected to expand the matres lectionis system and press even more consonants into double-duty as vowels.

If that wasn’t confusing enough, some of the glyphs that had been distinct in Aramaic ended up evolving into characters that looked the same. Imagine if the “l” and “t” in English ended up looking alike!

(Partly the glyphs changed so much because the Persians used Pahlavi for a long time: from about 150 BC up until 900 AD as a common language, and well into the Middle Ages as a liturgical language for Zoroastrian. There was enough time that various dialects of Pahlavi formed, including Inscriptional Pahlavi, Parthian, Psalter, and Book Pahlavi. The glyph shapes could look quite different; some were connected (cursive); some were disconnected. However, the differences in the script were essentially font differences, as all were used to write the Middle Persian language and all had Aramaic logograms.)

Finally, there were some sounds in Middle Persian that weren’t in Aramaic, so they overloaded some of the characters. “l” in Aramaic became “l” and “r” in Middle Persian.

While Cherokee, Cree, Brahmi and Korean are examples of some of the most clever writing systems, in my opinion, Pahlavi has got to one of the stupidest.

Links: Wikipedia, Ancient Scripts, Omniglot

http://www.ancientscripts.com/pahlavi.html