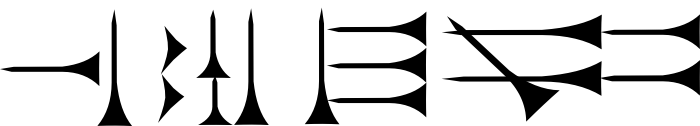

Because Chinese is a (mostly) logographic language, it isn’t obvious how to pronounce written characters. To deal with that, in 1913, the government of China developed a system to write the pronunciation of characters. Its official name is Zhuyin Fuhao, but everybody calls it “bopomofo” colloquially, after the names of the first four letters.

The People’s Republic of China abandoned it in the 1950s in favour of pinyin, a transliteration based on the Latin script, but bopomofo is still used in Taiwan.

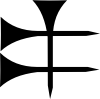

Bopomofo is not quite an alphabet (meaning separate characters for consonants and vowels, like Latin script), and not quite a syllabary (meaning that you have one character for each possible syllable, like Akkadian). Bopomofo is a semi-syllabary, which is very unusual. It has unique letters for initial consonants in a syllable (called onsets, which are usually consonants), but combines the rest of the syllable (called the rime) into one character. For example, there isn’t just one character which represents “r”. The “r-” at the beginning of a syllable is one glyph (the first sign in this post), but “-er” is a different glyph (shown to the left of this paragraph).

A friend of mine who grew up in Taiwan says that pinyin is much easier to use for computer text entry than bopomofo. Because English is so dominant in computer technology, the standard keyboard is designed for Latin script: a 26-letter alphabet with upper and lower case. By contrast, bopomofo has 21 onset characters and 17 rimes, with no upper/lower case, in addition to four marks for tones. This makes it clumsy to enter on the Latin-optimized keyboards.