Hryvnia

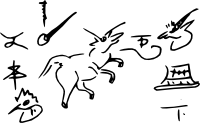

Many writing systems have a finite set of glyphs; you can write down a complete list and there are no others, except for the rare invention of new characters. But some writing systems have an open-ended set of glyphs; no matter how many you write down, it is routine to discover or invent a new one. Chinese script and its variants are prime examples of such open-ended scripts.

This leads to a big issue of writing technology. If you are writing by hand, you don’t care: you just draw any glyph you need. But movable type, and later digital fonts, have essentially finite glyph complements. It is not easy, especially for an end user, to add a new glyph to a font.

To make matters worse, a font may not contain all the glyhs in a writing system. The reference dictionaries of Chinese and Japanese contain some 50-70,000 characters; common Chinese and Japanese digital fonts contain some 20,000 characters today, and 15 years ago the standard was more like 8,000. (By comparison, a Japanese high-school graduate is required to know less than 2,000 characters, enough for adult communication.)

There were several causes for the limitations on font size. Many computer architectures were developed in the USA and other Latin-script territories, and initially addressed only Latin script needs. The capability for Chinese, Japanese, Cyrillic, Arabic, and other scripts were added later (and are still being added). Also, computer storage and processing were hideously expensive, and computer hardware and software developers could only afford to meet the most common needs of their their largest customers, not the complete needs of every potential user.

Hence publishers, and recently computer users, find sometimes that they want to use a character which is valid in their writing system but is not in their font. In Japanese these characters are called gaiji (meaning “outside character”).

Gaiji are not just a problem for Japanese and Chinese (and Korean, to a lesser extent): this is a significant problem for any scholars writing about extinct logographic writing systems like Chu nom or Sumerian.

If you are a computer geek, you might say, “ah, but Unicode solves that problem”. Unfortunately, Unicode doesn’t. Unicode encodes many characters; that is, it defines numbers to represent many characters in a string. It doesn’t make the font stretch to represent those characters. It also does not encode all characters, past and future.

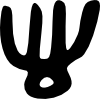

This problem is less common in European scripts, because glyphs are rarely added to these scripts. But “rarely” does not mean “never”. The glyph adorning this post is the Hryvnia, the Ukranian currency symbol, introduced in 2004. You might scoff at the Hryvnia, and figure that it isn’t that important to support the Hryvnia symbol, but I doubt you would say that about the Euro symbol, introduced in 1996.

NB: This is an issue of great interest to my family; my beloved husband’s team at Adobe System came up with a publishers’ tool for the gaiji problem, known as the SING Gaiji Architecture, available in Adobe Systems software between 2005 and 2010. (Disclaimer: I asked my husband to edit this post, and he did.) Adobe’s developer information page on “Gaiji — Supplemental Characters/Glyphs” has links to good overview papers. Many technologies for supporting gaiji have been tried, including stroke-based fonts, and ideograph decomposition.

Links: Wikipedia, “Gaiji: Characters, Glyphs, Both, or Neither?” paper (2002), “SING: Adobe’s New Gaiji Architecture” paper (2004), Sean Palmer essay, another ideograph decomposition proposal.

Gaiji

Hryvnia

Many writing systems have a finite set of glyphs; you can write down a complete list and there are no others, except for the rare invention of new characters. But some writing systems have an open-ended set of glyphs; no matter how many you write down, it is routine to discover or invent a new one. Chinese script and its variants are prime examples of such open-ended scripts.

This leads to a big issue of writing technology. If you are writing by hand, you don’t care: you just draw any glyph you need. But movable type, and later digital fonts, have essentially finite glyph complements. It is not easy, especially for an end user, to add a new glyph to a font.

To make matters worse, a font may not contain all the glyhs in a writing system. The reference dictionaries of Chinese and Japanese contain some 50-70,000 characters; common Chinese and Japanese digital fonts contain some 20,000 characters today, and 15 years ago the standard was more like 8,000. (By comparison, a Japanese high-school graduate is required to know less than 2,000 characters, enough for adult communication.)

There were several causes for the limitations on font size. Many computer architectures were developed in the USA and other Latin-script territories, and initially addressed only Latin script needs. The capability for Chinese, Japanese, Cyrillic, Arabic, and other scripts were added later (and are still being added). Also, computer storage and processing were hideously expensive, and computer hardware and software developers could only afford to meet the most common needs of their their largest customers, not the complete needs of every potential user.

Hence publishers, and recently computer users, find sometimes that they want to use a character which is valid in their writing system but is not in their font. In Japanese these characters are called gaiji (meaning “outside character”).

Gaiji are not just a problem for Japanese and Chinese (and Korean, to a lesser extent): this is a significant problem for any scholars writing about extinct logographic writing systems like Chu nom or Sumerian.

If you are a computer geek, you might say, “ah, but Unicode solves that problem”. Unfortunately, Unicode doesn’t. Unicode encodes many characters; that is, it defines numbers to represent many characters in a string. It doesn’t make the font stretch to represent those characters. It also does not encode all characters, past and future.

This problem is less common in European scripts, because glyphs are rarely added to these scripts. But “rarely” does not mean “never”. The glyph adorning this post is the Hryvnia, the Ukranian currency symbol, introduced in 2004. You might scoff at the Hryvnia, and figure that it isn’t that important to support the Hryvnia symbol, but I doubt you would say that about the Euro symbol, introduced in 1996.

NB: This is an issue of great interest to my family; my beloved husband’s team at Adobe System came up with a publishers’ tool for the gaiji problem, known as the SING Gaiji Architecture, available in Adobe Systems software between 2005 and 2010. (Disclaimer: I asked my husband to edit this post, and he did.) Adobe’s developer information page on “Gaiji — Supplemental Characters/Glyphs” has links to good overview papers. Many technologies for supporting gaiji have been tried, including stroke-based fonts, and ideograph decomposition.

Links: Wikipedia, “Gaiji: Characters, Glyphs, Both, or Neither?” paper (2002), “SING: Adobe’s New Gaiji Architecture” paper (2004), Sean Palmer essay, another ideograph decomposition proposal.