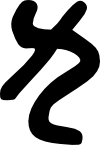

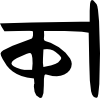

Takri — also called Takkari, Takari, and Tankri — descended from Sharada. Sharada evolved gradually, and at some point it started being called Devasesa; in the sixteenth century, a version called Takri (used for commerce) became distinct enough from Devasesa (used for administration and ceremony) that it got a separate name.

Then, about a century later, Takri started being used for administrative purposes in some principalities in northern India. As there were a number of different small princedoms, there was not a strong incentive to standardize across princedoms, and thus there is quite a lot of variation among the glyph shapes in different princedoms, and occasionally different spoken languages with unique phonemes gave rise to unique characters. However, the users of the different variants consider the variants to all be “Takri”. (By analogy, Danish and French have characters that do not appear in English, yet English, Danish, and French readers would all consider that the script they write in is Latin script.)

In the 1800s, Takri started losing ground to Devanagari, and ceased being used for official purposes in the mid 1900s. It is now little-used and in danger of going extinct.

Links: Wikipedia, Ancient Scripts, Unicode proposal